Compensation stock options explained

Despite what critics say, stock option grants are the best form of executive compensation ever devised. You have to have the right plan. Twenty years ago, the biggest component of executive compensation was cash, in the form of salaries and bonuses.

Stock options were just a footnote. Now the reverse is true. With astounding speed, stock option grants have come to dominate the pay—and often the wealth—of top executives throughout the United States.

Michael Eisner exercised 22 million options on Disney stock in alone, netting more than a half-billion dollars. It would be difficult to exaggerate how much the options explosion has changed corporate America. But has the change been for the better or for the worse? Certainly, option grants have improved the fortunes of many individual executives, entrepreneurs, software engineers, and investors. Their long-term impact on business in general remains much less clear, however.

Option grants are even more controversial for many outside observers. The grants seem to shower ever greater riches on top executives, with little connection to corporate performance. They appear to offer great upside rewards with little downside risk. And, according to some very vocal critics, they motivate corporate leaders to pursue short-term moves that provide immediate boosts to stock values rather than build companies that will thrive over the long run.

As the use of stock options has begun to expand internationally, such concerns have spread from the United States to the business centers of Europe and Asia. Options do not promote a selfish, near-term perspective on the part of businesspeople.

Options are the best compensation mechanism we have for getting managers to act in ways that ensure the long-term success of their companies and the well-being of their workers and stockholders.

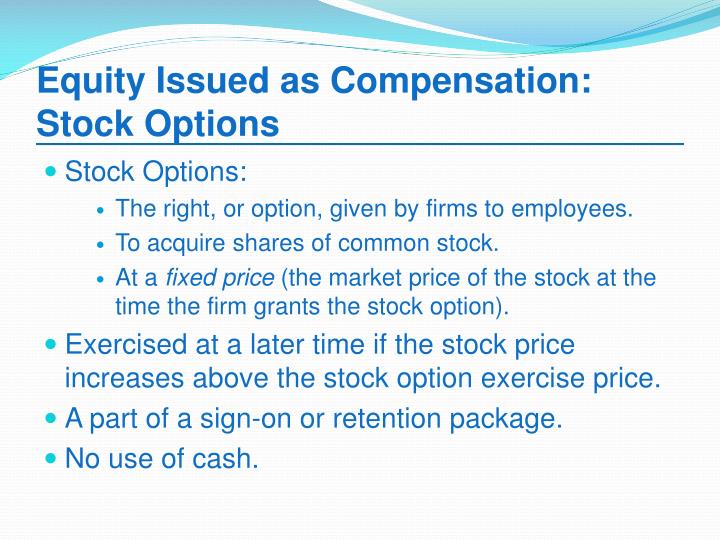

Stock options are bafflingly complex financial instruments. As a result, companies often end up having option programs that are counterproductive. I have, for example, seen many Silicon Valley companies continue to use their pre-IPO programs—with unfortunate consequences—after the companies have grown and gone public. The lesson is clear: The options issued to executives usually have important restrictions.

Most, but not all, have a vesting period, usually of between three and five years; the option holder does not actually own the option, and therefore may not exercise it, until the option vests. Option holders do not usually receive dividends, which means they make a profit only on any appreciation of the stock price beyond the exercise price. The value of an option is typically measured with the Black-Scholes pricing model or some variation.

Black-Scholes provides a good estimate of the price an executive could receive for an option if he could sell it. Since such an option cannot be sold, its actual value to an executive is typically less than its Black-Scholes value. The last two factors—volatility and dividend rate—are particularly important because they vary greatly from company to company and have a large influence on option value. They lose their value quickly and can end up worth nothing.

But the potential for higher payoff is not without a cost—higher volatility makes the payoff riskier to the executive. Companies reward their shareholders in two ways: Most option holders, however, do not receive dividends; they are rewarded only through price appreciation.

Since a company that pays high dividends has less cash for buying back shares or profitably reinvesting in its business, it will have less share-price appreciation, all other things being equal. Therefore, it provides a lower return to option holders. Research by Christine Jolls of Harvard Law School suggests, in fact, that the options explosion is partially responsible for the decline in dividend rates and the increase in stock repurchases during the past decade.

If you are an executive, you can raise the value of your options by taking actions that increase the value of the stock. The Effect of Volatility and Dividend Rate on Option Value Option value is stated as a fraction of stock price. For a framework on how to measure the value of nontradable executive and employee stock options, see Brian J. Hall and Kevin J. The main goal in granting stock options is, of course, to tie pay to performance—to ensure that executives profit when their companies prosper and suffer when they flounder.

Many critics claim that, in practice, option grants have not fulfilled that goal. Executives, they argue, continue to be rewarded as handsomely for failure as for success. As evidence, they either use anecdotes—examples of poorly performing companies that compensate their top managers extravagantly—or they cite studies indicating that the total pay of executives in charge of high-performing companies is not much different from the pay of those heading poor performers.

The studies are another matter. Virtually all of them share a fatal flaw: As executives at a company receive yearly option grants, they begin to amass large amounts of stock and unexercised options. When the shifts in value of the overall holdings are taken into account, the link between pay and performance becomes much clearer. By increasing the number of shares executives control, option grants have dramatically strengthened the link between pay and performance.

For both measures, the link between pay and performance has increased nearly tenfold since Given the complexity of options, though, it is reasonable to ask a simple question: The answer is that options provide far greater leverage. For a company with an average dividend yield and a stock price that exhibits average volatility, a single stock option is worth only about one-third of the value of a share. The company can therefore give an executive three times as many options as shares for the same cost.

In addition to providing leverage, options offer accounting advantages. The accounting treatment of options has generated enormous controversy. On the other side are many executives, especially those in small companies, who counter that options are difficult to value properly and that expensing them would discourage their use. The response of institutional investors to the special treatment of options has been relatively muted. They have not been as critical as one might expect.

There are two reasons for this. First, companies are required to list their option expenses in a footnote to the balance sheet, so savvy investors can easily figure option costs into expenses. Even more important, activist shareholders have been among the most vocal in pushing companies to replace cash pay with options.

In my view, the worst thing about the current accounting rules is not that they allow companies to avoid listing options as an expense. That discourages companies from experimenting with new kinds of plans. As just one example, the accounting rules penalize discounted, indexed options—options with an exercise price that is initially set beneath the current stock price and that varies according to a general or industry-specific stock-market index.

Although indexed options are attractive because they isolate company performance from broad stock-market trends, they are almost nonexistent, in large part because the accounting rules dissuade companies from even considering them.

The idea of using leveraged incentives is not new. Most salespeople, for example, are paid a higher commission rate on the revenues they generate above a certain target. Such plans are more difficult to administer than plans with a single commission rate, but when it comes to compensation, the advantages of leverage often outweigh the disadvantages of complexity. You also have to impose penalties for weak performance. The critics claim options have unlimited upside but no downside. The implicit assumption is that options have no value when granted and that the recipient thus has nothing to lose.

But that assumption is completely false. Options do have value. Just look at the financial exchanges, where options on stock are bought and sold for large sums of money every second.

A Guide To CEO Compensation

Yes, the value of option grants is illiquid and, yes, the eventual payoff is contingent on the future performance of the company. But they have value nonetheless. And if something has value that can be lost, it has, by definition, downside risk. In fact, options have even greater downside risk than stock. Consider two executives in the same company.

One is granted a million dollars worth of stock, and the other is granted a million dollars worth of at-the-money options—options whose exercise price matches the stock price at the time of the grant. The executive with options, however, has essentially been wiped out. His options are now so far under water that they are nearly worthless. Far from eliminating penalties, options actually amplify them.

The downside risk has become increasingly evident to executives as their pay packages have come to be dominated by options. Take a look at the employment contract Joseph Galli negotiated with Amazon.

The risk inherent in options can be undermined, however, through the practice of repricing. When a stock price falls sharply, the issuing company can be tempted to reduce the exercise price of previously granted options in order to increase their value for the executives who hold them. Although fairly common in small companies—especially those in Silicon Valley—option repricing is relatively rare for senior managers of large companies, despite some well-publicized exceptions.

Again, however, the criticism does not stand up to close examination. For a method of compensation to motivate managers to focus on the long term, it needs to be tied to a performance measure that looks forward rather than backward.

The traditional measure—accounting profits—fails that test.

It measures the past, not the future. Stock price, however, is a forward-looking measure. Forecasts can never be completely accurate, of course. But because investors have their own money on the line, they face enormous pressure to read the future correctly. That makes the stock market the best predictor of performance we have. But what about the executive who has a great long-term strategy that is not yet fully appreciated by the market? Or, even worse, what about the executive who can fool the market by pumping up earnings in the short run while hiding fundamental problems?

Investors may be the best forecasters we have, but they are not omniscient. Option grants provide an effective means for addressing these risks: That delay serves to reward managers who take actions with longer-term payoffs while exacting a harsh penalty on those who fail to address basic business problems.

Stock options are, in short, the ultimate forward-looking incentive plan—they measure future cash flows, and, through the use of vesting, they measure them in the future as well as in the present. If a company wants to encourage a more farsighted perspective, it should not abandon option grants—it should simply extend their vesting periods.

Their directors and executives assume that the important thing is just to have a plan in place; the details are trivial. As a result, they let their HR departments or compensation consultants decide on the form of the plan, and they rarely examine the available alternatives. While option plans can take many forms, I find it useful to divide them into three types.

The first two—what I call fixed value plans and fixed number plans—extend over several years. The third—megagrants—consists of onetime lump sum distributions. The three types of plans provide very different incentives and entail very different risks. With fixed value plans, executives receive options of a predetermined value every year over the life of the plan.

Employee Stock Options: Definitions and Key Concepts

Fixed value plans are popular today. Fixed value plans are therefore ideal for the many companies that set executive pay according to studies performed by compensation consultants that document how much comparable executives are paid and in what form. But fixed value plans have a big drawback.

Because they set the value of future grants in advance, they weaken the link between pay and performance. Executives end up receiving fewer options in years of strong performance and high stock values and more options in years of weak performance and low stock values. The stock price has doubled; the number of options John receives has been cut in half. He ends up, in other words, being given a much larger piece of the company that he appears to be leading toward ruin. For that reason, fixed value plans provide the weakest incentives of the three types of programs.

I call them low-octane plans.

Whereas fixed value plans stipulate an annual value for the options granted, fixed number plans stipulate the number of options the executive will receive over the plan period. Under a fixed number plan, John would receive 28, at-the-money options in each of the three years, regardless of what happened to the stock price.

Here, obviously, there is a much stronger link between pay and performance. Since the value of at-the-money options changes with the stock price, an increase in the stock price today increases the value of future option grants.

Likewise, a decrease in stock price reduces the value of future option grants. Since fixed number plans do not insulate future pay from stock price changes, they create more powerful incentives than fixed value plans.

I call them medium-octane plans, and, in most circumstances, I recommend them over their fixed value counterparts. Now for the high-octane model: While not as common as the multiyear plans, megagrants are widely used among private companies and post-IPO high-tech companies, particularly in Silicon Valley. Megagrants are the most highly leveraged type of grant because they not only fix the number of options in advance, they also fix the exercise price.

Shifts in stock price have a dramatic effect on this large holding. Every few years since , Eisner has received a megagrant of several million shares. Since the idea behind options is to gain leverage and since megagrants offer the most leverage, you might conclude that all companies should abandon multi-year plans and just give high-octane megagrants.

When viewed in those terms, megagrants have a big problem.

Look at what happened to John in our third scenario. After two years, his megagrant was so far under water that he had little hope of making much money on it, and it thus provided little incentive for boosting the stock value.

And he was not receiving any new at-the-money options to make up for the worthless ones—as he would have if he were in a multiyear plan. It would provide him with a strong motivation to quit, join a new company, and get some new at-the-money options. Ironically, the companies that most often use megagrants—high-tech start-ups—are precisely those most likely to endure such a worst-case scenario. Their stock prices are highly volatile, so extreme shifts in the value of their options are commonplace.

And since their people are in high demand, they are very likely to head for greener pastures when their megagrants go bust.

Indeed, Silicon Valley is full of megagrant companies that have experienced human resources crises in response to stock price declines.

Such companies must choose between two bad alternatives: Silicon Valley companies could avoid many such situations by using multiyear plans. The answer lies in their heritage. Before going public, start-ups find the use of megagrants highly attractive. Accounting and tax rules allow them to issue options at significantly discounted exercise prices.

The risk profile of these pre-IPO grants is actually closer to that of shares of stock than to the risk profile of what we commonly think of as options. When they go public, the companies continue to use megagrants out of habit and without much consideration of the alternatives. But now they issue at-the-money options. What had been an effective way to reward key people suddenly has the potential to demotivate them or even spur them to quit. Some high-tech executives claim that they have no choice—they need to offer megagrants to attract good people.

Yet in most cases, a fixed number grant of comparable value would provide an equal enticement with far less risk. With a fixed number grant, after all, you still guarantee the recipient a large number of options; you simply set the exercise prices for portions of the grant at different intervals. By staggering the exercise prices in this way, the value of the package becomes more resilient to drops in the stock price. Switching to multiyear plans or staggering the exercise prices of megagrants are good ways to reduce the potential for a value implosion.

Small, highly volatile Silicon Valley companies are not the only ones that are led astray by old habits.

Large, stable, well-established companies also routinely choose the wrong type of plan. But they tend to default to multiyear plans, particularly fixed value plans, even though they would often be better served by megagrants.

Think about your average big, bureaucratic company. The greatest threat to its well-being is not the loss of a few top executives indeed, that might be the best thing that could happen to it.

The greatest threat is complacency. To thrive, it needs to constantly shake up its organization and get its managers to think creatively about new opportunities to generate value.

The high-octane incentives of megagrants are ideally suited to such situations, yet those companies hardly ever consider them. The bad choices made by both incumbents and upstarts reveal how dangerous it is for executives and board members to ignore the details of the type of option plan they use. While options in general have done a great deal to get executives to think and act like owners, not all option plans are created equal.

Frank Denneman

Only by building a clear understanding of how options work—how they provide different incentives under different circumstances, how their form affects their function, how various factors influence their value—will a company be able to ensure that its option program is actually accomplishing its goals.

If distributed in the wrong way, options are no better than traditional forms of executive pay. In some situations, they may be considerably worse. In cliff vesting, the vesting periods of all option holdings are collapsed to the present, enabling the executive to exercise all his options the moment he leaves the company. Hall is the Albert H. Gordon Professor of Business Administration and.

Your Shopping Cart is empty. March—April Issue Explore the Archive. Tying Pay to Performance. A version of this article appeared in the March—April issue of Harvard Business Review. About Us Careers Privacy Policy Copyright Information Trademark Policy Harvard Business Publishing:. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.